The evolution of my cargo bike

My cargo bike was borne out of my desire to take my dog cycle touring. I wanted a genuine touring cargo bike. To make for a good holiday, I wanted my cargo bike to be light, stiff, fun to ride, comfortable, and safe for the dog, and I wanted to have the possibility of adding a roof over the cargo bay. Obviously, given I was making a bike from scratch, I decided on a geometry that would fit me perfectly. I also knew that a cargo bike made to this pretty specific brief would also excel in my daily life, taking the place generally occupied by a car.

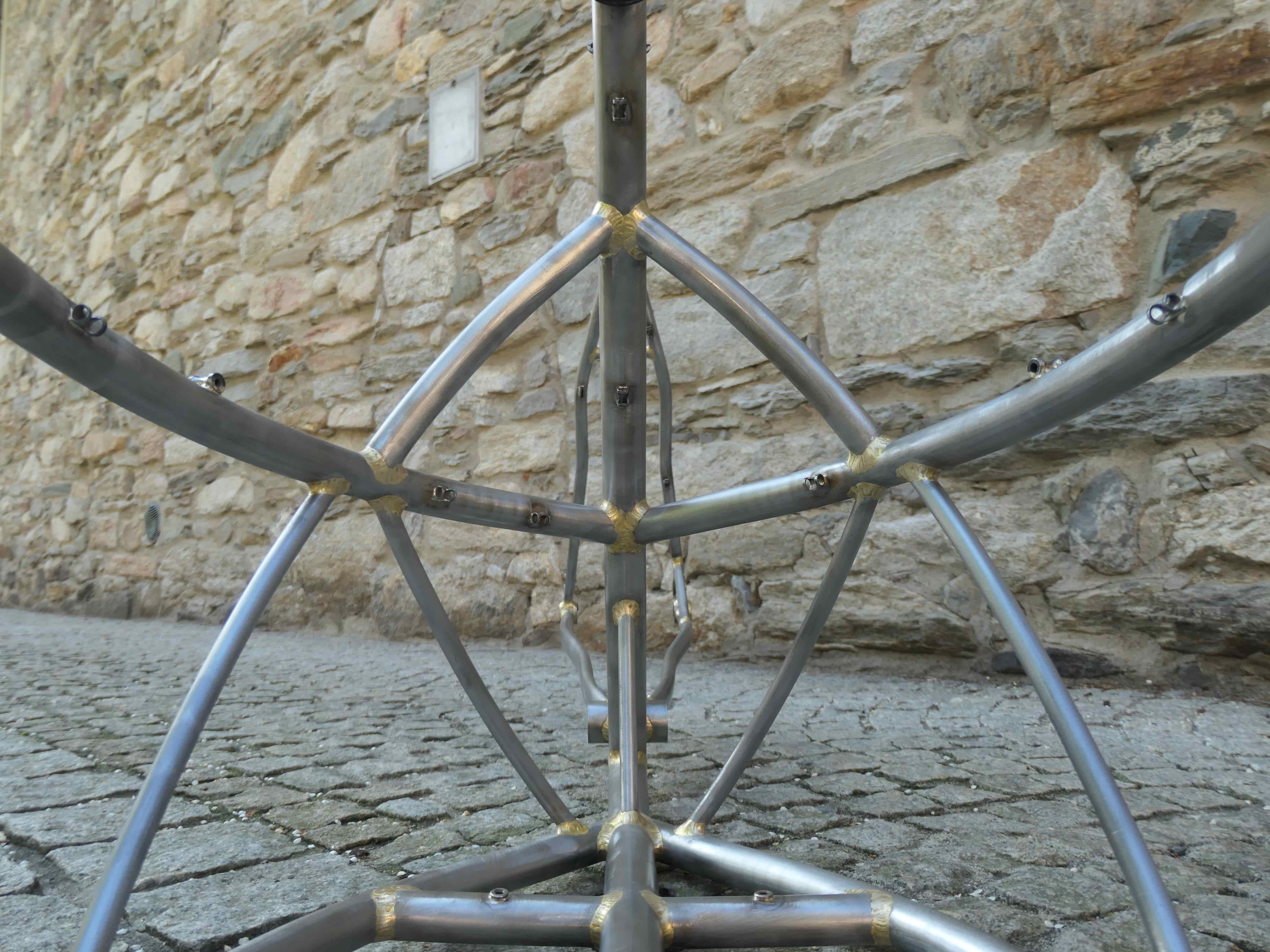

In order to make the cargo bike as stiff as possible, I decided to use a trellis design, giving the cargo bay “depth”1. This depth not only renders the bike stiff and light, but it also serves a practical purpose: It provides a comfortable protected area for my dog when she travels with me and also keeps the shopping or any other loose items from falling off the bike when I’m transporting stuff that isn’t a dog. The roof over the cargo bay does not keep my dog entirely dry, but it does give her some shade from the sun and keeps the majority of the rainfall off her. I think she appreciates it.

It was clear from a structural perspective that if I wanted a stiff cargo bike, its overall length should be minimized3.

To give me more flexibility in the design of the bike4 and to decrease the overall weight, I knew I wanted cable steering. Many cargo bikes have what I refer to as a “floating head tube” design, where the head tube with the handlebars floats above the cargo bay; this minimizes the length of the bike for a given cargo bay length. Cable steering also gives a wonderful sensation while riding the bike. Almost all the play in the system can be removed, giving a responsive feel to the ride. And to some extent, it also gives the possibility to alter the tension in the cable to personalize the feel of the bike. It was clear from the outset that I definitely wanted two sets of cables for safety5.

Not only is a trellis a wonderful way of creating a light, stiff structure; it is also rather beautiful. Nearly 20 years prior to starting building bicycles, I worked as a mechanic in a garage that specialized in Ducati motorbikes. I was always struck by the beauty of the trellis frame they used and how striking the contrast was compared with the industrial-looking aluminium “perimeter” frames that other motorbikes used. I wanted to have a bike that resembled in a way that beautiful motorbike frame. I initially started drawing a cargo bay that, when viewed from above, had a hexagonal cargo bay with two vertical walls. This design was really close to the Ducati Monster frame, and it would have also rendered making the trellis (more or less) straightforward. Later in the development of my design, I came across the beautiful Frances Cycles cargo bike, which has a more sweeping curve. I fell in love with this aesthetic, and it also solved a problem of wrinkling I was having at the sharp bends on the thin-walled tubing, so, I changed my design to include a continuous curve. This rendered the trellis far harder to construct but repaid the hard work with a wonderful flowing aesthetic. Over time, I added more trellis beams to increase the practicality of the structure as well as reinforcements linking the planar part of the cargo bike (the bit that resembles a normal bike) with the cargo bay walls to increase the feeling of unity between the two parts. The design of the frame is now more or less fixed; every now and then I make a change to some details, but the design of the frame is now mature.

Many companies use large-diameter tubing to make a fairly stiff cargo bike. To keep the weight relatively low, when using large-diameter tubing, it is typical to use tubes with thin walls. This means the stiffness is limited by the fact that making the walls of the tubes too thin means they become fragile. This limit is particularly restrictive for steel tubing, which is a shame because steel has a very high resistance to fatigue. The answer to this problem was a trellis design. Trellis frames are amazing: you can achieve extremely stiff, lightweight structures, and you can do it without using large-diameter, thin-walled (fragile) tubing. This means that steel tubing can be used, which, in my opinion, is the best possible structural material for making a cargo bike6. The only downside is that it takes a lot of time to make these incredible structures.

Another early decision that I made was to use a conventional fork rather than a hub-steering system. Here, for me it was always clear: The fork was the right choice. I wanted to have a wide choice of standard components, and I am always attracted by simplicity. The bicycle fork has a long history, and for around 100 years, it has also been used on cargo bikes; it has been well tested. The fork also provides a natural way to create the “depth” of the cargo bay, which renders my cargo bike so stiff. I’m certain a well-made hub-steering system can be fun to ride and reliable, but I felt the fork was the right choice for me.

The choice of standards to use on the frame was tricky. I initially went for the traditional choices: rim brakes, 36-mm head tubes, QR axles, etc. Over time, I realized that, especially when offering a bike for sale, wherever possible, a bike should be “future proofed”. For this reason, when in doubt, I now tend to use standards that will remain in use for a long time to come. Some examples of this thinking are the use of thru-axles (which, having tried them extensively, I now think also offer real benefits for a cargo bike, including stronger wheels and greater stiffness), threaded bottom brackets (they remain in use, while pressfit standards come and go), and head tubes with 44-mm internal diameter (EC34 seems to be increasingly less common, while EC44/ZS44 remains in widespread use). Of course, given each bike is made individually by me, these things can be personalized, but the starting point is a considered one that makes a lot of sense from a practical point of view. Having learnt many valuable lessons through my years of carefully considering every aspect of my design, I can give one piece of advice that I am sure very few would have questioned in the first place: Don’t make a cargo bike with rim brakes!

Having used my cargo bikes for many years, and many many kilometres, I believe it is as perfect as it can be for the things I use my bike for. It fits a week’s worth of shopping for two people that eat a lot, my dog loves it and is safe in there, it transports oddly shaped objects with ease, and it is just fun to ride. I think, and I don’t deny my bias, that it is the most beautiful cargo bike on the market, and that it does a good job combining a classic elegance with modern touches. As you probably guess from having read all this, I am hugely proud of my cargo bike, and I sincerely hope you will like it too.

Notes

1 For the structure nerds: The stiffness of a structure is due to the material you make it from and the geometry of the structure. I make steel bikes, and steel is a stiff material. The trellis design is a brilliant architecture to achieve a high “geometric stiffness”. When you couple a set of tubes such that the deformation of the tubes is “coupled” (i.e., they deform together), you increase the geometric stiffness (or second moment of area2) of the structure. Placing these coupled tubes the correct distance apart and using a sufficient number of “coupling tubes”, you can create a very stiff and lightweight structure. Another way to do this is to use large-diameter tubing, but this is typically heavier and less stiff.

2 The second moment of area is a way to quantify the effect of geometry on the mechanical properties of a structure. For example, if you take a 30-cm ruler and hold it so that the flat surface is facing you and try to bend it so that the deflection is away from you, it bends easily; if however, you take the same ruler and have the thin edge face you and try to bend it away from you, you’ll find it hard. The difference lies in the geometry, and this difference is quantified by the second moment of area. A large second moment of area means a stiff structure.

3 For the structure nerds: The stiffness of many structures, including a beam supported by two end pivots (kind of like a bike, whose frame is supported by the two axles), scales inversely to the cube of the length of the structure. Thus, doubling the length will decrease the stiffness of the structure by a factor of eight. For this reason, it’s essential to minimize the length of a cargo bike.

4 Cable steering gives flexibility in the design of a cargo bike as you don’t have to have a long bar linking the steering and the forks. Typically, this long bar runs under the cargo bay, which means you have to have a long head tube permitting the steerer tube to protrude at the bottom of the bike. This is a big design restriction, and it also leaves the steering system open to striking the floor on uneven ground.

5 Cable-actuated controls have been used for a very long time in aviation. They are also used in cargo bikes, and there is no doubt about their safety.

6 Steel, titanium, and aluminium all have relatively similar strength-to-weight and stiffness-to-weight ratios. For a given weight of tube per unit length, aluminium and titanium, however, can be used to make larger-diameter tubing while maintaining a reasonable wall thickness (necessary for impact resistance). This large-diameter tubing leads to a high second moment of area and consequently a high stiffness. (If stiffness was the only criteria, this means steel would not be the best material to use for a bike frame, but of course it’s not the only criteria – a bike has also to be strong). If instead, one creates a trellis design where the stiffness comes from the separation and coupling of the elements in the frame, rather than the stiffness of the individual members, the diameter of the tubing is not so important for the stiffness of the structure. This means that steel is once again comparable to the other two metals in terms of the stiffness/strength-to-weight ratios. Then, steel has another two properties that make it excel: It is far better at resisting fatigue than other materials, and it has a “feel” that is just wonderful in a bike. (This “feel” I suspect is down to its dynamic properties combined with the small-diameter tubing, but I don’t know this for sure. But there is a reason why steel-framed bikes will always remain sought after.) I suppose that what I want to say is simple: Due to its fatigue properties and wonderful “feel”, I personally would only ever consider buying a steel-framed trellis-based cargo bike.

If you have any questions/comments about this post, please contact me here.